FRONT COVER

Image: color photo of Anne

Title, subtitle, author

KAIBETO MEMORIES

A Trader’s Daughter Remembers

Growing Up on the Navajo Reservation

in Remote

Northern Arizona

1936-1960

by Elizabeth Anne Jones Dewveall

INSIDE FRONT COVER

Blank

Page 1 TITLE PAGE (right side)

Image of Anne cut from "Anne at Gas Pump"; permission granted

Title (suggest use of Adobe font --Sego Print Bold just for title Kaibeto Memories)

Kaibeto Memories

A Trader’s Daughter Remembers

A Trader’s Daughter Remembers

Growing Up on the Navajo Reservation

in Remote

Northern Arizona

1936-1960

by Elizabeth Anne Jones Dewveall

Page 2 TITLE PAGE REVERSE (left side)

Cataloging in Publication or Library of Congress Control Number

(Provisional publisher)

VistaBooks LLC

637 Blue Ridge Road

Silverthorne, CO 08498

email@vistabooks.combr

Copyright 2022 by Elizabeth Ann Jones Dewveall

ISBN: 978-0-89646-103-1.

Page 3 DEDICATION PAGE (right side)

Dedicated to

Julia and Ralph Jones

Traders at Kaibeto

my parents

--Eliaabeth Anne Jones Dewveall

Page 4 DEDICATION PAGE REVERSE

image printed at 90 degrees bottom toward gutter: Overall view of Kaibeto Trading Post

Here at Kaibeto Trading Post is where Elizabeth Anne spent much of her childhood. The house where she lived, obscured here by trees, was attached to the trading post (shown on the left). An interior doorway passed from the house to the trading area, keeping traders on-call almost constantly. The main entrance to the trading area, flanked by windows on each side, shows in the center of the more prominent building. The structure on the left is the warehouse for storing supplies and traded merchandise such as hides. This picture is a bit unusual in that it was not uncommon to see in the view here not only horses, but wagons and even a pickup. Natives might also linger, socialize, await a family member's lengthy shopping session, or play card games before or after their trading activity, sometimes all day. (August 1948)

Pages 5 and 6 FOREWORD--starts on right-side page and continues on back: 854 words

FOREWORD

by Elizabeth Anne's cousins

Our cousin Elizabeth Anne spent her early years on the Navajo Indian Reservation at Kaibeto Trading Post. She was the daughter of the trader there. Her trader-father, Ralph Jones, and her mother, Julia, operated this supplier of white-man’s goods to local Indians at a time when there was no other source for supplies in that barren land. Bluffs, mesas, and sandy desert were the landscape around this place, then among the most isolated in the United states with something like seventy-five miles to the nearest railroad track over rut roads. For the Natives, producing a living on this land required ingenuity and perseverance, and the trading post provided some of what was needed to make life a bit easier.

Elizabeth Anne’s time at the post was from her birth in 1936 until the early 1960s. Her playmates were often Native children. When Elizabeth Anne reached school age she lived during school sessions in Winslow with her Aunt Zada, Uncle John, and their two daughters so she could attend schools there.” But when at the trading post during school breaks and summer vacations, she, too, became a trader, helping with sales and operation of the post. She thus had a youth that was unusual for a girl in America and which led to experiences involving interactions among two cultures.

Several of us in the family have prodded Elizabeth Anne to “write a book” about her Kaibeto experiences, but only recently during COVID downtime did she begin to jot down her memories as they came to her day by day. She posted notes on Facebook as she produced one little story after another to share with friends and family and to record the contribution her parents made to the trading post’s history. Finally, Elizabeth Anne has agreed to allow her Kaibeto memories to be gathered into book, and many of us are grateful.

Though Elizabeth Anne’s wider family includes writers of various kinds, many of us feel she is the best writer among us. Her prose is direct, clear, and has a nice bounce to it. One feels immediately present in her scenes, and her sentences often seem to have a smile on their faces. Sometimes she brings forth a genuine belly laugh without even trying.

Now others can enjoy our cousin’s lively, down-home accounts of childhood and teenage years in that remote spot in northern Arizona. The tales, in fact, include a time when Elizabeth Anne and her husband Bob managed Kaibeto Trading Post just as her mother and father did when she was a young girl there. It’s hard to imagine anyone now alive knows more of the Kaibeto trading operation than Elizabeth Anne does.

In, with, and under some of Elizabeth Anne’s memories, we have specific, firsthand instances of respect, friendship, and even deep caring between the trader’s family and their customers. And occasionally there is a hint of resentment toward white culture when it seemed not to value Navajo ways. So, along with her delightful telling about her life “on the Rez” as she calls it, Elizabeth Anne has given historians and cultural anthropologists a primary source of information and insight into the ongoing interactions between whites and native peoples in America.

Our cousin wants us to keep in mind that her stories do not portray Navajo ways today. She suspects they now use credit cards or smart phones to pay for things, and she knows many in the younger generation who have been to fine schools and gone on to college and the professions. “The old ways,” she says, “are mostly gone.”

Readers also do well to be aware that Elizabeth Anne’s memories do not proceed in chronological order from her earliest days onward but are set down as she remembers them during those recent weeks of intense COVID concern. Toward the end, she gives dates for the day the memory was written down. As she remembers we are reminded that the memories came interspersed with her daily activities many years later. With but few minor changes, we have remained faithful to what Elizabeth Anne wrote.

When we were in our early teens, the two of us cousins had a great adventure living with Ralph, Julia, and Elizabeth Anne at Kaibeto for a week or so. We rode Indian ponies, watched weavers at work, saw the dog get struck by a rattlesnake (the dog lived), pumped gas, and went trembling into the dark cave to bring in a fresh supply of “total chosie,“ which is what we thought Navajos called soda pop. So it is our special pleasure to help make a book out of our cousin’s captivating stories from her early life. We hope you, too, will enjoy them, learn from them, and gain a deeper appreciation for the life Elizabeth Anne and her parents lived out there in Kaibeto. May we also come to understand something of the Navajo culture and the people who have lived it in their wide, barren, and beautiful land.

--Bob and Bill Jones (or Bobby and Billy as we were called when we stayed at Kaibeto Trading Post)

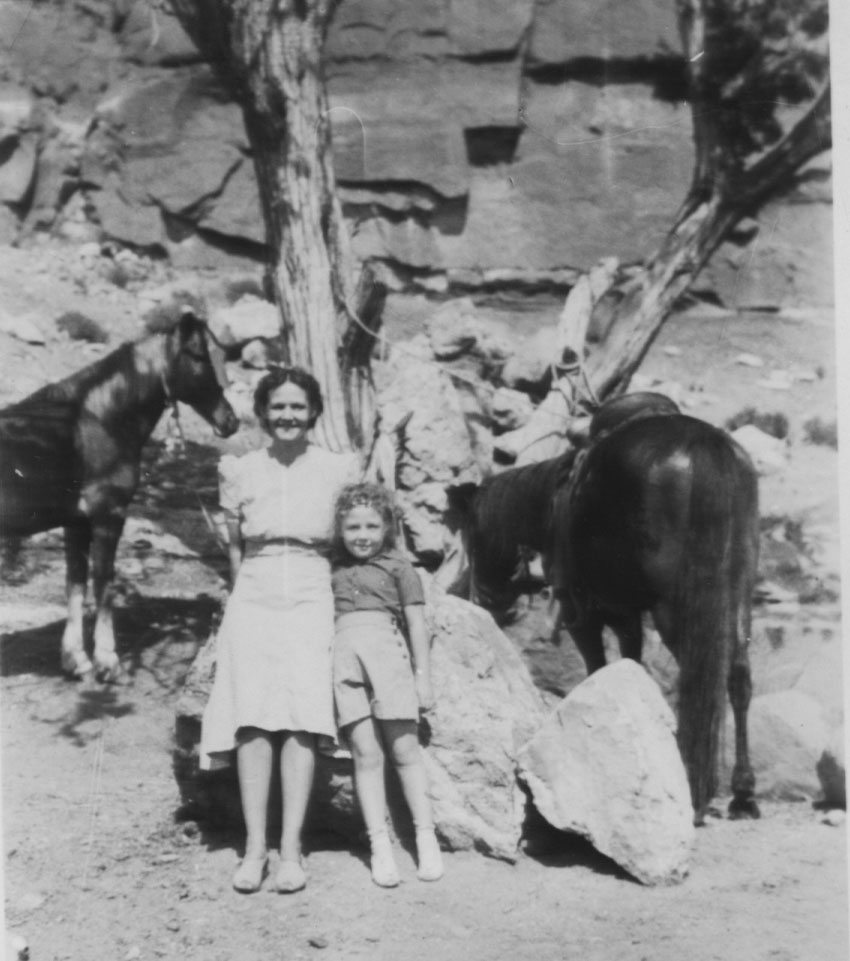

Page 7 right-side PAGE available for pictures

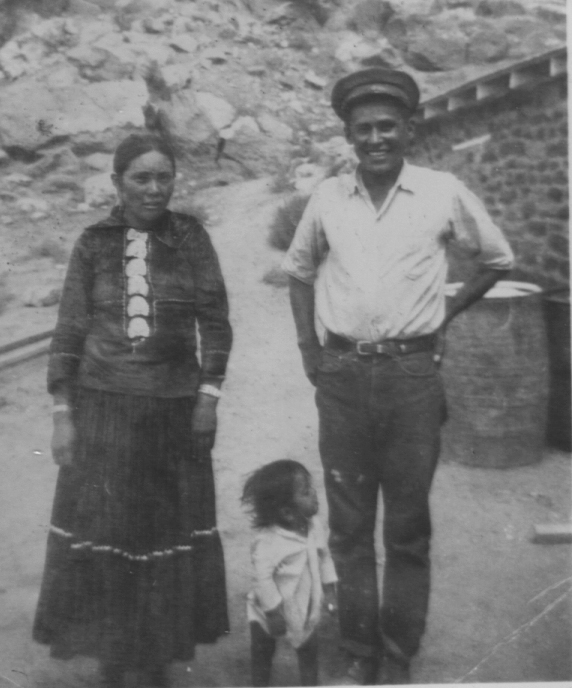

Elizabeth Anne holding Daddy’s hand, while Ralph is in his typical "trader's uniform” for being merchant, warehouseman, mechanic, and more. 1943.

Elizabeth Anne and Julia in "trader's uniform" for trading in the store. circa 1943.

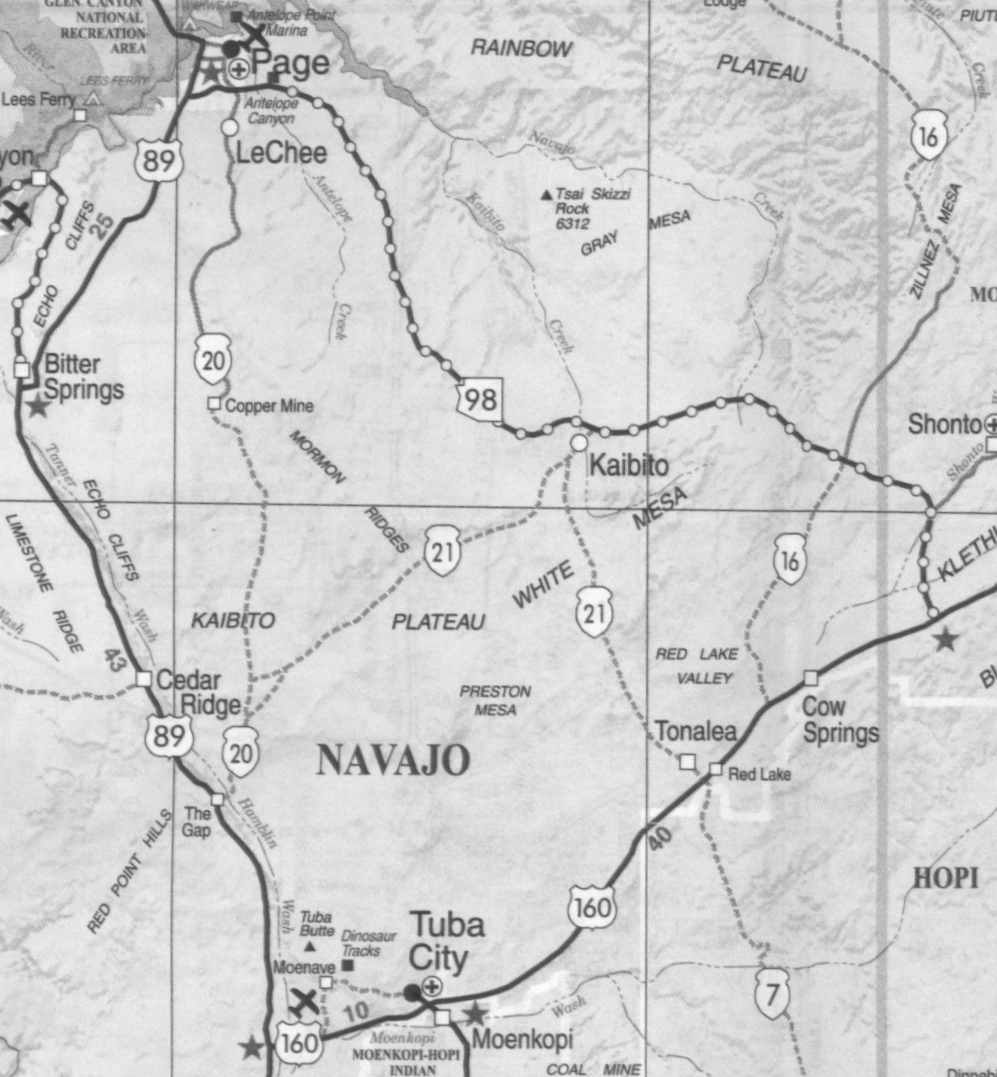

Page 8 MAP on left-side page

map from Arizona Guide, 2010, used by permission from Arizona Office of Tourism

KAIBITO/KAIBETO

Navajo words like kaibeto were initially not written. This may explain why different spellings got attached to different places. Not far from the trading post is a spring that has long been called Kaibito Spring and which may explain why the post was built where it was. Such springs in this region are not unlikely to have willows. From the web page of the K’ Ai’ Bii’ To’ chapter of the Navajo Nation we learn that the word “Kaibeto” or “Kaibito” derives from the old Navajo phrase that is expressed in writing as K’ Ai’ Bii’ To’. The web site also tells us this can be translated “willow in the water.”

In today's world two spellings of Kaibeto/Kaibito are used for different features: The trading post from far back in time has been spelled Kaibeto as is the Kaibeto Indian School, but the creek that occasionally runs past these places is shown on government maps as Kaibito, as is Kaibito Spring, Kaibito Plateau, and the town of Kaibito but which today has the Kaibeto post office. In Kaibeto Memories the separate spellings that have traditionally been applied to separate features have been used.

Page to end of book BODY TEXT--begins on right-side page

Kaibeto Memories--

A trader's daughter remembers

Growing up on the Navajo Reservation

in Northern Arizona

1936-1960

by Elizabeth Anne Jones Dewveall

Editors: Each memory Elizabeth Anne recorded during her COVID down-time is separated by a space from the next, in the sequence she remembered them but not necessarily in the sequence in which the events occurred.]

Catching up on newspaper reading today and feeling sad about the plight of the Navajo people during this pandemic. When my parents were traders on the Rez all those years ago, most Navajo families hauled their water, making it an extremely precious commodity. For about thirty percent of the population this is still true today. A fifty-gallon barrel of water for a week's supply does not make for the recommended frequent hand washing.

People tell me I should write a book about the more than twenty-five years my folks manned that desolate, but beautiful trading post. When you arrived at Kaibeto, you had to leave by the same road you came, for it was truly the end of the line. We had few visitors and those we didn't know, especially if they were Anglo, were looked at with suspicion. During those days, more than one trading post went up in flames along with their proprietors. It was never, ever a Navajo who caused such harm. So, yes, I do have enough trading post yarns to outlast this pandemic and tomorrow I will attempt to bring you one featuring my inimitable father. For today I would ask for your prayers for these dear people who were so good to our family for so many years.

It's one of those days with a multitude of interruptions, so the story I promised yesterday will be tomorrow's tale. Never fear, I have just finished listening to the latest political hoopla surrounding our current situation and it reminded me of a bit of political collusion on the reservation more than a half century ago. After the Suffragettes finished their worthy work, there was still one group in our nation who were denied the privilege of voting. This travesty was eventually corrected, and Native Americans were allowed to go to the polls. Like the rest of us, these tribal citizens first had to register to vote. And in order to register there had to be a registrar. Each trading post had a suitable candidate in the local trader. Thus, my father was duly sworn and left to figure out on his own how to properly process this important steppingstone among a people whose only ID might be a thumb print.

My dad was as honest as any man who ever lived, but he was also a card carrying, straight ticket, die hard Democrat. After explaining the importance of selecting a president and other dignitaries with his rather limited Navajo vocabulary, he failed to find the right words to explain the little box on the registration form which indicated party preference. Needless to say, from that day forward, every Navajo voter in nearly fifteen square miles became a member of the Democratic Party. As terrible as that sounds, it really did nothing to spoil the good old USA ideal of all men being equal. The trader at Tonalea, located about twenty miles to the south was as staunch a Republican as Daddy was a Democrat and he also suffered a loss of his Navajo vocabulary when it came to checking the Political Party box.

Today's trader adventure is a bit indelicate, so if you are the blushing type, just skip on over to the lady who is giving instructions on how to fashion a face mask out of old brassieres. The old-time trading posts were three walled affairs with an area in the center called the "bull pen." This pen was surrounded by a counter with a railing over it so the customer was obliged to stand at a distance from any desired purchase. Shopping was done one item at a time with the shopper pointing to what was needed and the trader then putting that item on the counter. This could be, and often was, an all-day process.

Trading posts sold everything from canned peaches to horseshoe nails so every inch of space behind the counter was precious and shelves were stocked from ceiling to floor. Daddy always stocked the shelves next to the ceiling with unbreakable goods such as boxes of oatmeal or cornmeal. He became very adroit at flicking those down by sliding a broom handle behind them and catching them inches from the floor. This was big entertainment for our customers and always brought an appreciative response. Thus encouraged, Daddy constantly improved his performance, sometimes making a half turn before making his catch at the last possible microsecond.

Then (you can start blushing now) came the advent of women's personal products. Mother had a hard time convincing Daddy that those blue boxes should be included in the inventory, but he finally ordered just one case. Since these were not breakable, they joined the oatmeal and cornmeal on the topmost shelves. And there they stayed and stayed and stayed some more until Daddy could not resist telling Mother that he was right and should not have listened to her about ordering such things. Mother informed him that of course they were not going to sell because everything that came off those top shelves was accompanied by a performance second only to Vaudeville and no shy Navajo lady was going to risk such embarrassment. She recommended moving them to a quiet eye level corner where they could be bought with no fanfare. This meant displacing some canned milk and other important big sellers and was done very grudgingly. Still the pretty blue boxes gathered dust unless Mother or I happened to be in the store. Finally, Daddy realized that no Navajo lady was going to buy such things from a man. So if Mrs. Nez had obviously finished her shopping but remained standing quietly by her purchases, he would bound up the little steps to our living quarters and holler for Mother or me to get down in the store because he was quite sure Mrs. Nez had one more purchase to make. This was always fun for me because as I was making sure the blue box was modestly contained in a plain brown paper bag, the recipient and I would always giggle together as if we were the only ladies in the universe who were privy to such secret things.

I have to confess I nearly wrote this one in my nightie. One little chore led to another and first thing I knew I was sans shower and no earrings and it was noon! I could feel both my mother and my Aunt Zada peering over my shoulder. But on to a very little-known aspect of Navajo trading. In those early days many of the Navajos were herders in every sense of the word. Their flocks of sheep and goats and sometimes even a few cattle were immense, and their lives depended on them.

In spring we bought their wool and in the fall they sold us lambs. If a lamb or goat was slaughtered for personal use, every inch of the animal was put to good use. Even so, occasionally one of our customers would come bearing a sheep or goat skin or even a cow hide. I don't know if Daddy paid fifty cents or five dollars for such because it was not a part of the enterprise I wanted to know about. Daddy stacked these offerings in a far and gloomy corner of our huge warehouse and covered them loosely with a tarp. Getting anywhere near that corner was not a treat for the senses!

Enter Mr. H H Baker who lived in Winslow and who just happened to be my Sunday School teacher when I took my turn at being schooled there. Mr. Baker was employed by Babbitt Brothers (who more or less ran all that part of Northern Arizona in those days) to do such important tasks as getting those animal hides out of trader's warehouses and on their stinky way to become purses or belts. Not only was he a conscientious judge of hides, Mr. Baker (along with his wife) was convinced that the soul of every child entrusted to his teaching was his Godly responsibility and might end up in eternal trouble if he neglected them in any way. Thus, when I was home on the reservation for the summer, Mr. Baker's visit always involved a review of several missed Sunday School lessons. Mr. Baker always had several posts to visit during whatever day he showed up, so due to time constraints, he had to multitask. I was told to sit on a bale of hay while he sorted the sheep skins from the goat skins, the stench and aroma of untanned pelts growing ever thicker while Jesus walked on water or Jericho came tumbling down. When he was finished, Mother always had a nice lunch waiting for him which he ate with great appreciation while I wondered if I would ever be hungry again.

Not many folks can say their earliest memory was formed by stepping on a rattlesnake, but that early childhood scenario has been frozen in my brain for more than eighty years. My grandparents were visiting, and that morning my grandmother had firmly planted my white high-topped lace up shoes upon my feet before I took my first step. Back then, everyone believed that toddlers had weak ankles and that sort of shoe was the answer to the problem. So be it summer or winter, we all had to wear them, brown for boys, white for girls and ugly as sin. Even so, my detested pair may well have saved my life.

I had just escaped the heat of the kitchen and was walking down a little hill close to the back door, when I felt something squishy under my well shod feet and looked down to discover I was standing atop a big pile of something that reminded me of scales on a fish. I was old enough to know that where there were fish there should be water, so I rushed inside to announce the unusual phenomenon of a fish in our arid back yard. All four adults quickly abandoned the breakfast table as I headed out the door ahead of them to point out my find. They were greeted by the ominous bone chilling buzz only a king size rattler can produce.

My step grandfather, a very genteel jeweler and watch maker, quickly pulled up one very well pressed pant leg in preparation for crushing the snake's head with the heel of his shoe. My father, seeing the danger and impossibility of this move, gave Daddy Self a shove that propelled him all the way to the clothesline pole. With his other hand Daddy grabbed the hoe, kept by the back door for just this sort of occasion, and separated the snake from its head. My mother and grandmother provided appropriate female acoustics while I, thinking that somehow all this violence was my fault, sought shelter behind a nearby washtub.

I don't recall anything else about that day, but it is interesting to note that many years later when my husband Bob and I were running the trading post, our older daughter, seeking to escape nap time, stepped bare footed on a huge bull snake which was sunning himself on the porch step. She also ran to tell me there was a big fish out there. Why three-year-olds equate snakes with fish is beyond me, but at this particular spot in history, we have plenty of time to ponder the answer to that question.

In yesterday's posting I mentioned something called a clothesline pole. It has occurred to me that there may be a few of you out there who have no idea what that might be. Back in the "good ole days" before the advent of General Electric or Whirlpool, God did the clothes drying. This required a long heavy wire strung between two stationary poles. Clothes were pinned on this wire by clever little gadgets called, of all things--clothes pins. If the line was long enough and the laundry large enough, first thing you knew that wire stretched, and your newly scrubbed skivvies were dragging in the dirt. Thus, the clothesline pole which had a ring screwed in its top and could be moved at will to prop up the line and prevent such disasters.

My mother had enough Native American genes to be able to assimilate quite well into the surrounding culture. but she did strictly adhere to the old adage about "washing on Monday, Ironing on Tuesday, mending on Wednesday,” etc. I am sure there were some ladies in her generation who would have said that mantra could be found in the Bible right along with "money is the root of all evil." There are a lot of things about progress of which we can be critical, but I am thankful I can throw a load of clothes into an electric dryer on a Saturday and not feel guilty. But for today, just for today, we are going to honor my mother's convictions and leave those sheets and towels and Daddy's long johns flapping in the breeze while I find time to send a note or two to some Winslow friends I am sure are risking it all for their fellow tribe members [as they help those stricken by the virus].

My parents were not church attenders as there were no churches to attend any closer than fifty miles away at Tuba City. That may not sound like a formidable distance to us today, but each of those fifty miles was a bone jarring, axle breaking challenge on a road which could change its route daily depending on the last sandstorm. Until the early 50's most trading posts were open from sunrise to sunset seven days per week. When they did begin closing on Sunday, that day was a welcome respite to catch up the multitude of chores involved in maintaining a trading post. Thus, my mother who had absolutely no talent as far as reading future events became a pioneer in our new phenomenon of reaching people online to further their spiritual growth.

We had a radio of sorts. [To prepare her spiritual messages,] every weekday morning at nine o'clock Mother popped up out of the store or dishpan or whatever was claiming her attention and glued her ear to the little radio where a fellow named Al Salter (if I remember correctly) held forth on his "Hour of Power." This was strictly her time with the Lord and no interruptions were permitted. Unless I was home to give Daddy a hand, Hosteen Littleman's horse had to wait for its hay breakfast and John Manygoats's pickup had to park patiently by our lone gas pump. No one ever seemed to mind, and I can't help but think that time she spent might have been one of the reasons our post, although one of the most desolate, was spared all of the catastrophes experienced by so many others.

This is the way we wash our clothes, wash our clothes, wash our clothes, early Monday morning. This is the way we iron our clothes, iron our clothes, iron our clothes, early Tuesday morning. A few of you might be old enough to remember that little ditty. Even though it sounds frivolous, when I was a child, it was a serious reminder of how housekeeping duties were supposed to be conducted.

I have a very vague memory of Mother using a set of irons which were heated on the wood stove, then clamped onto a handle until they cooled and had to be replaced. I think Mother called them "sad irons" but that may not be accurate. What I do have is a clear memory of, and perhaps a scar or two from her next iron. I believe it was made by Coleman (the lantern people) and was equipped with its own little gas tank which was attached to the back of the iron. A tiny pump was used to build up pressure until one could ignite the innards which burned brightly just like the gas grills of today.

There were only a few minor problems. Since the heating unit was mid-section of the iron, the tip remained cool. If you pumped the pressure up high enough to heat the entire iron and tackled the wrinkles on a collar, the rest of your shirt usually became decorated with an iron shaped scorch mark. But this was nothing compared to what happened if you let your arm relax for even a second. Almost as soon as the iron was lit, the small rear gas tank became about the same temperature as the bottom of the iron. Ironing day always involved a few blisters and a definite change in my mother's usual upbeat personality. Daddy and I pretty much stayed in the trading post every Tuesday.

LYSOL! That really was what I was going to write about today and now there is all this hubbub over it [concerning harmful chemicals]. Forget all that. Lysol is another of those products which was around during our trading days and did play a rather prominent part. With all the emphasis on sanitizing in our present state, you may not be ready for this one, but here goes. Every trading post had a drinking bucket sitting on the closest counter to the entrance. Most people traveled long, dusty miles to get there and were very thirsty when they arrived. This big galvanized bucket was filled with fresh water each morning and maybe several times during the day. In the interests of sanitation there was a large dipper inside the bucket. Instead of dipping the provided tin cup into the clean water, the user poured it into the cup which was then used by everyone.

Tuberculosis was rampant on the Rez in those days and my mother had every reason to fear it. She had experienced the disease and was one of those folks who were sent "out west" to prolong her life by maybe a few months. (She stretched that out by over fifty years.) She recognized the danger of this mode of refreshment and did her best to combat it. Her weapon of choice? Lysol, of course. Back then there was only one Lysol product which came in a little brown bottle and poured out in a thick goo which instantly turned white when added to water. Every night our bucket got a thorough scrubbing with a Lysol solution ten times stronger than recommended and the poor little tin cup was completely submerged until the next day dawned. The surrounding counter was also thoroughly swabbed and left dripping. Mother would have dismissed the wipes we use today as not worthy of notice. Daddy and I both hated the noxious odor of that solution but our complaints were ignored. That area always smelled faintly of Lysol and although I know she rinsed the bucket and cup thoroughly every morning, I am also certain the water at our trading post had a slightly different taste than at some of the others.

A bit of a change today for some blessing counting. Yesterday we had a visit (we kept all the covid rules) from our younger daughter and her husband. They brought our dinner and as we "mimed" our parting hugs, I couldn't help but think of the first hug this child ever had nearly sixty years ago.

Carole was our "trading post" baby and a third addition to our family. Elaborate plans were made for her safe arrival, and a cabin was rented where my parents would stay with our other girl and boy as the delivery time grew near. The local medicine man kept telling me we were going to way too much trouble because he could take care of me just fine. In retrospect, we probably should have listened.

The big day arrived, and Daddy drove me to the hospital, and calmly stayed with me through labor. He was the one who realized it was time for me to finish up the job we had begun and alerted the nursing staff. Then, in a few short moments, due to the incompetence of the doctor and staff, we came very close to having a still born baby. (Something about a coffee break?). It took a lot to get my dad riled up, but when he realized that I had been left alone in the delivery room, the most skilled matador in Mexico would have been shaking in his cape if he had to confront Daddy.

When the crisis was over, the doctor handed the baby in all her newborn ickiness to my father and told everyone if that old man didn't know that she was okay they were likely to have him as a patient. I think his real reason was that he knew that with his arms full of newborn baby, my father would not be able to chase him down and strangle him. Carole got her first embrace from the grandfather she came to adore. God looked after us that day and continues to do so through all three of our precious children. I am so thankful.

Looking at our car gathering dust in the carport this morning made me think of my dad's old maroon Buick which never lacked a nice protective coating of Arizona dust and sometimes sported several layers of mud/clay on each fender. It was either a 1940 or '41 two door affair with a tiny back seat. He acquired it shortly before WWII broke out, so he was stuck with it for the duration. During its ten-year life span it served us well even though when traded in it was more baling wire than Buick.

Its most important feature was a massive trunk which was sacred ground and never to be meddled with by wife or daughter. Along with all the jack handles and other paraphernalia which always comes with cars, it held other equally important items. Stuffed into one corner were at least a dozen gunny sacks. Alongside those was another gunny sack which was filled with several cans of Vienna sausages, tins of sardines, boxes of saltine crackers, a big box of matches, small pieces of kindling tied together, rolled up newspaper, a roll of toilet paper, and a wicked looking pocketknife. Several blankets hid a set of chains in another corner. Atop all this was a medium size axe and full-size shovel. Most important, there was a huge canteen of water which was always full.

Thanks to the gunny sacks which provided great traction when thrown under a mired wheel, after one applied the jack, I never got to experience a delicious repast of crackers and sardines while being stuck in sand or mud overnight. There were a couple of times that it took Daddy so long to extract us from whatever predicament we were in that I did get to drink from the canteen. Alas, he wasn't all that particular about changing the water!

The spring I graduated eighth grade, my father came to fetch me driving a black Buick Roadmaster. On the way home he proudly announced that his new acquisition came equipped with something called Dynaflow, so I should easily learn to drive it. A typical Jr High graduate, I was feeling quite grown up, but never dreamed Daddy meant any time that summer. Next morning, amidst her loud protests of "Ralph, she is too young", Daddy left Mother minding the store and we were off for our first driving lesson.

Kaibeto had an airport (that is another story), which was overgrown with tumble weeds but still reasonably flat. It really was easy to stop and start and steer on that clay packed surface (no shifting involved with Dynaflow) so very quickly Daddy directed me to the main road where I was taught the intricacies of reservation driving. Important rules like find a wide spot and pull over when you saw a cloud of dust moving toward you as that meant another vehicle was approaching and would need to pass. Always slow nearly to a stop and hold your breath when you had climbed the hill to the "divide" because the road was rocky there and so no way to know if a vehicle was coming at you head on. And NEVER, NEVER slow down if you see a sand dune up ahead.

When we returned to the trading post, Daddy handed me the keys and informed me that from now on it was my responsibility to pick up the mail. The nearest post office was twenty-four challenging miles away over that same "practice road" and every Monday and Friday were mail days. Mother was still muttering protests as she accompanied me on my first run. She never went along again. I don't know if that was out of fear for her life or because she realized there really was little danger for me.

By the time I turned sixteen many Navajos had reason to drive on state highways so it was decided they should have a license like everyone else. The examiner showed up one morning and now I really was old enough to drive, so I eagerly awaited my turn to be tested. My heart sank when I looked out the window and saw that this test fellow was putting up traffic cones and having all the applicants drive backwards around them and also was requiring them to parallel park. Daddy and experience had taught me many things about driving by then, but we had completely neglected the little R on the gear shift display. With sinking heart, I went to start the black monster, but the only response was that little "click, click" which comes when the battery is kaput. Hot and tired and looking longingly at the road out of our little valley, the man asked me how long I had been driving. I told the truth, and he handed me my license as he told me he figured since I was still alive, I probably would also survive out where there were real roads. To this day I still can't back a car more than a few feet.

I think I was about four years old when I became the "total chosie" (that is what the Navajo word for soda pop sounded like to me) girl at the trading post. Due to coming-of-age rites or the very important curing ceremonies, there were times when a great many extra Navajos gathered in our vicinity. Our "bull pen" would become so packed that Mother had no choice but to join Daddy in waiting on the crowd.

Alas, I was too young to be left to my own devices in the living quarters. The solution to this dilemma was probably against the law, but I think quite ingenious. Our cash drawer was built into the lowest of the many shelves at the front of the store. Soda pop cost a dime, so mother eliminated the penny place, pushed all the other coins down one place and taught me that if someone paid me with a fifty-cent piece then I was to put that fifty-cent piece in its place and for change give them back the coins from those remaining in the row. That would be a quarter, a dime and a nickel. If someone paid in pennies, I was told to just throw them in the bottom of the drawer. I had a little stool to climb on and Daddy installed a bottle opener down on my level. About all I had to remember were the words for black (Coke), orange (Nesbitt’s), or red (strawberry) and of course that a dime required no change. Everyone soon learned that paying for pop with anything but coin caused a delay while a grown-up was found to make change.

Navajos of that day trained their children to watch sheep when they were at a tender age, so no one even thought to turn my parents in for any sort of child abuse. I thought it was great fun. I didn't learn much, as many years later when I was managing a convenience store, I allowed my fifteen-year-old son to help out in the pop cooler. I caught the dickens from my boss and Lee had to be banished immediately. That worked out okay as the minute he turned sixteen he started working in the grocery business and remains there today. My parents would be quite proud.

Kaibeto Trading Post was built smack dab into the side of a Mesa. So I am guessing that the cave carved into that Mesa was the beginning of its construction. The door to that cavern loomed as an ominous dark hole situated at the far end of our huge warehouse. I am quite sure, like the walls, the floor was dirt. I never lingered long enough to find out. The cave's temperature remained the same all year and it was used for storing all the "total chosie" we talked about yesterday, plus huge bags of apples, onions, and potatoes.

My father had read me every fairy tale ever written. Thus I was sure that cave was inhabited by all sorts of creatures which not only went "trip, trap, trip, trap” as they followed you to your doom but also shouted, "fee, fie, fo, fum" while they sharpened their knives in preparation to cutting you into bite sized pieces. After all, they had to be somewhere, and the cave would be an ideal habitat. When I grew strong enough to lift a case of pop, Daddy would send me to the cave to fetch it. I never let him know how terrified I was, and I never saw so much as an errant spider in the place.

It was Daddy who showed up for breakfast one morning looking a bit pale and unnerved. He had made his routine supply trip into the cave, sans flashlight, as usual, and came eye to eye with a huge snake. This was a very friendly reptile who just happened to be hanging from some protrusion in the roof. Happy for the company, the snake dropped down around Daddy's shoulders, giving him a big hug as he slithered off into warehouse. 'Twas only a bull snake, but I never saw Daddy go in the cave again without flashlight in hand.

One of my daughter's friends asked me today if Kaibeto still existed. Sadly, it has gone the way of at least ninety percent of the old-time trading posts. Last time we were in the area, there was nothing left but a good portion of the pump house and a few walls from the old government school. The trading post had been so decimated that I had a hard time figuring out what went where. I like to think that the huge tin roof, the thousands of stones, and the Arbuckle coffee box windowsills had all been carted off to make many hogans or sheep camps more livable. There is, however, still a place called Kaibeto Trading Post and it is built in an area we called "up the hill" where the ground is level and there are no sand dunes to slog over or washes to carry you away.

The original Kaibeto was built very close to where two washes converged. I guess the proper word is arroyo, but we called them "Little Wash” and “Big Wash". Big wash can be found on some old maps and shows that it drained a very large area northwest of Kaibeto. Little wash had no such map distinction, but if you walked along it for a couple of miles you were treated to some of the most amazing rock cathedrals and slot canyons God ever created. The only problem with this arrangement was that when it stormed, Kaibeto became more or less an island. It didn't have to rain at Kaibeto itself to make those washes produce bountifully. We knew that when the sky was dark to the north it was very likely we would soon be hearing the crashing and pounding of seething muddy water pushing huge boulders and even trees ahead of it. Very rarely did both washes perform together, but when they did, we always wondered if this would be the time our gasoline tank would get pulled out of the ground. It never was.

The last bit of what passed for a road to the trading post was right across the washes. After every storm Daddy had to round up a crew, hand out the shovels (and the "total chosie") and rebuild. It was not an easy job and sometimes took a couple of days. We still had customers, but they didn't buy as much when it had to be carried across the slimy wash bottom to a pickup parked a quarter of a mile away. I suspect that the last time Kaibeto changed hands, the current trader decided it would be much more sensible to move the whole operation up the hill. That certainly would have been a very wise business decision, but it cost him a life in one of the most beautiful little valleys any of you can imagine.

In this darn pandemic, it has been some time since we have discussed our various wardrobes as we stay in our abodes, knowing we won't be viewed by anyone but close family. Yesterday I donned my usual garb of a pair of knit pants and a rather nondescript top. My husband promptly declared that he didn't realize I had a doctor's appointment. When I asked him why he thought I was going somewhere, he replied. "You got dressed this morning."

For the past week I have been trying out several floor length lounge dresses which have hung in my closet since before the advent of our oldest great grand. (She is 22). Even though properly accessorized with earrings, he must have thought they were night gowns. Today I am making sure he knows which end of me is up by wearing one of my favorites, the mauve one which proclaims, "At my Age I Need Glasses" and features some fancy long stemmed goblets bearing assortments of exotic fruits. I just love the color!

There are many pictures of me during my preschool phase dressed in typical Navajo garb. At age three I was featured on the back cover of Standard Oil Magazine dressed like every little Navajo girl. Posing by our lone gasoline dispenser, I also was sporting a ton of wonderful turquoise jewelry Daddy must have borrowed from the pawn cupboard. Truth be told, I often wore overalls, and that was not considered proper for little girls in those days.

Mother must have strayed into the men and boys section of "Monkey Wards" for my clothes, but she must have kept those articles at home, for none of my aunties or my grandmother appear in pictures with me unless I was properly clad in a dress. I was in Junior High when my Winslow mom (Aunt Zada) allowed me to own one pair of slacks--in case we decided to go on a picnic. She also purchased just one pair for herself in order to be modest for bicycle riding. No one ever knew about the pair of men's Levi's awaiting my arrival at home from school every summer. Stiff as boards, it took about two weeks of constant wear to break them in, but after that they were perfect for every occasion.

I don't remember this story at all, but my mother retold it frequently, so it must be true. For many years our trading post was owned by the Richardson family. The Richardson's were a downright dynasty when it came to owning trading posts. Many of you have probably visited the crown jewel of their efforts, a place called Cameron located on Highway 89 about forty miles north of Flagstaff. So it was natural that we stopped at Cameron frequently, for both business and pleasure. The Richardsons knew how to throw a good party, especially at Christmas. This was during the Shirley Temple era when the parents of every daughter around Shirley's age hoped their little girl could also board the band wagon to stardom. Besides trading, Cameron's other claim to fame was its excellent location for filming many of Hollywood's early productions. By the Christmas before I was three, my mother had taught me to recite Clement Moore's "The Night Before Christmas" in its entirety. Everyone thought that was quite marvelous and so it was suggested that I perform at the upcoming Christmas party.

The best part was that Samuel Goldman (or some other Hollywood big wig) would be in attendance and would probably beg my parents to sign a contract so he could use my phenomenal talents. The time came and Mother pushed me front and center and told me to say my poem. Instead of heeding her plea I stomped my feet and yelled. "The Night Before Christmas! I am tired of saying that dammed thing and I am not going to do it again--ever." Exit--stage right and the end of a movie career which never began. As I said before I don't recall any of this, but I do know that a few years ago it resurfaced in my brain when our great grandson Jayden was literally forced to learn the "damned thing" for a school assignment. I was able to sit in the back of the classroom and mouth the words to him every time he got a bit lost. We earned an A for his performance.

My husband and I have been competing to see who required the most medical attention lately. How blessed we are compared to all those years ago at the Trading Post. The nearest hospital for the Navajo was fifty miles away at Tuba City, but that wasn't much of a problem. They were not going to go there anyhow. As we have mentioned before, any structure in which a person expired was deemed a "ghost house" and never used again. The Bureau of Indian Affairs didn't quite go along with this belief--even the government is not so extravagant with our tax money that it is going to abandon a hospital each time it loses a patient.

The old generation of Navajo were not about to enter a building which was inhabited by the "chindi" of the departed. The local medicine man reigned supreme, and his curing ceremonies did seem to work quite well. There was also a public health nurse whose main occupation was frustration over how little cooperation she received for her suggestions on such things as personal hygiene, proper nutrition, and even birth control. It never entered her mind that a fifty-gallon barrel of water was a week's supply for most families. Her one big success was during a pandemic of sorts. An outbreak of typhoid or maybe it was diphtheria--one of those diseases we seldom think about today, took the life of several little ones and the good nurse was able to persuade the tribe that the white man had the answer to preventing more such tragedy. Old Hosteen Gishibetoh, who was considered the leading elder in our parts, allowed her to inoculate him and we soon had a line awaiting her ministrations. I was not pleased when my mother placed my pale face in that line and then returned to a very busy day at the store. There was no paperwork, no questions about allergies, just an agonizing jab in the upper arm. I spent the next two days wishing my left arm would fall off.

Three years ago today, God and our children provided this manufactured "hogan" we love so dearly. One hundred twenty years ago today my children's maternal grandmother made her debut in Petersburg, Pennsylvania. How she came from there to the trading post at Kaibeto some thirty-four years later will never be quite clear, but once there she never wanted to be anywhere else. The Navajo people of that era were gentle, generous, and trusting. Alas, as with any culture, there were a few rotten apples in the barrel. Because of intense clan and family pride, those sorts were referred to as someone who acts as if he has no relatives.

I was away at college when Mother, who was a rather shy lady, starred in an incident that was picked up by the "moccasin telegraph" and shared around every campfire from Tuba City to Navajo Mountain. One afternoon when the post was very busy, a young man who had obviously been sampling the local "firewater," (more about that in another story) began making a very unNavajo nuisance of himself. Daddy told him to take his obscenities and rough manner outside.

When the young man refused, Daddy, took hold of his arm, intending to give the fellow a little help to finding some fresh air. The unthinkable happened and Daddy found himself on the floor, twisted in such a way that any self-defense was impossible. This altercation just happened to take place next to the counter under which axe handles were stored. It took Mother less than a second to grab one of those new axe handles and give the fellow such an embarrassing thrashing that he probably shopped at Shonto for the rest of his life. He didn't know how blessed he was that we always sold axe heads and axe handles separately. Seeing someone manhandle her man might have clouded Mother's judgment a bit when it came to choosing a proper weapon.

From that day forward, among other traders, Mother became known as "Axe Handle Julia." The Navajo, who always called her "Hosteen's Wife" or "Little Sister" gave her their silent approval and never changed her name at all. HAPPY HEAVENLY BIRTHDAY, MOTHER. You have been gone for a bit more than 38 years, but I still write this with tears running down my face.

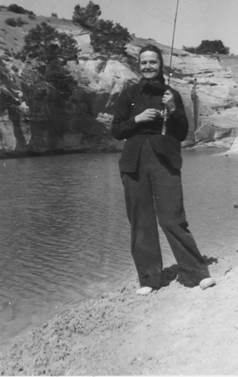

Considered a sacred place by the Navajo, Navajo Mountain, north of Kaibeto was an always present reminder of the beauty of that area. There was a trading post there also, but Barry, the fellow who owned it, wasn't around all that much. His main residence was in Phoenix, but he did stop by to visit us occasionally. Barry's favorite activity was to join the yearly mule train which consisted of the mules used for the Grand Canyon tourist excursions. This long trek took several days, and the group always spent one night at Kaibeto where they enjoyed Mother's pinto beans, cornbread, and leg of lamb.

Barry and his pals were as Republican as Daddy was Democrat, and the political discussions went far into the night. They all bedded down in our living room to sleep beneath one of my parent's prize possessions which was a smiling portrait of Franklin D Roosevelt. Daddy enjoyed his repartee with Barry but once remarked to us that he hoped Barry never tried to run for public office because his ideas were pretty crazy, and he really should be paying more attention to his trading post.

I hadn't seen Barry in a long while when we ran into each under unusual circumstances. It was my senior year in high school, and the annual Freedom Foundation awards were televised in Phoenix. I had won a bobby pin sized trophy for an editorial I had written in the Winslow High Bulldog Barks. I have forgotten what Barry's award was, but it must have been pretty important for they saved him for last and gave him a long introduction. When he stepped in front of the camera, he didn't wait for the host to finish introducing us, but pronounced, "Oh,I already know this girl and I have spent many a night sleeping at her house--ER--on the floor-ah--I mean in the living room." The further it went the worse it got while seventeen-year-old me prayed the TV studio would collapse around us. My only consolation was that Winslow as yet did not have TV and my friends would not be witnessing this most embarrassing moment.

Revenge came quite a few years later when my first husband, our nine-month-old daughter, and I ran into Barry while shopping at a drugstore in Prescott. By this time Barry really was enjoying quite a political career and he seemed delighted to see us. Back then it was popular for politicians to kiss every baby they ran across, so of course our dear friend couldn't wait to get his hands on SueAnne. She was not inclined to go to strangers and pushed back toward me, pulling her plastic pants (anyone remember those?) askew which rendered them useless when Barry pulled her toward him. She left a lovely puddle down the front of him! By the way, Barry's last name was Goldwater.

Sometime during the thirties, the Bureau of Indian Affairs built a small two room school directly behind our trading post. It also housed whatever poor beleaguered teacher found herself in the position of school marm. None of these ladies were married and perhaps had shown some ineptitude in their employment and thus were sent to a place where they could cause no further problem. For certain, what they all had in common was total ignorance of the Navajo culture and language.

Back in those times it was thought that the sooner we made speaking English the only option available to Native Americans the better. No thought was given to some sort of methodology to accomplish this miracle. Teachers arrived with Dick and Jane and Puff and Spot and the expectation that every Navajo child would soon be saying, ''Look, look. See Spot run,'' just like the Anglo children. The day school idea didn't work well anyhow for attendance was always sporadic. When your hogan is ten miles away and transportation consists of pony or wagon, tardiness was the order of the day. It was also thought that each child should be showered and then dressed in government provided clothing before proper lessons could begin. At least the BIA was wise enough to always hire a young Navajo couple to help with all this preparation. The poor teacher still struggled and, with a couple of exceptions, none lasted more than one year.

One of those exceptions was Mrs. Williams, a widow lady from Tucson. A spicy old gal, she didn't give a hoot about Dick and Jane and invented all sorts of ways to bridge the communications gap. She didn't care if she couldn't understand the kids or they her, she just loved them. She also loved the solitude of our location and our little family. She and mother had their own private book club and read everything from "Gone with the Wind" to "God's Little Acre." Of course you know how this tale is going to end. Much to her disgruntlement, disgust and horror, the BIA transferred Mrs. Williams. She was so angry that the day she left we were startled by a loud pounding on the back door. There she stood, gasping for breath from her effort to push a government issue bookcase, much admired by Mother, across our sandy yard. She told us the BIA would never miss it and she wanted Mother to have it. Stolen goods accepted, she and Mother exchanged a last hug. And that is why to this day the most well-built piece of furniture we "own" has PROPERTY OF US GOVT stamped on its back.

Not often, but every once in a while, my daddy could be downright ornery. One morning another one of the day school teachers desperately pounded on our back door tearfully asking for Mother's advice. One of her students had drawn a very detailed and a bit more anatomically correct than necessary, picture of a nude male. Poor Miss Moore, who had no idea how to handle the situation, was wringing her hands and in a state of apoplexy. The Navajo were and still are an extremely modest people. But when a dozen family members live together in an area the size of most Anglo kitchens, children are bound to see a few things we whites would think unseemly. Mother tried to explain to Miss Moore that the child had probably drawn the picture in all innocence, never dreaming she would think he had done something bad.

Before Mother could finish calming the poor distraught maiden lady, my dad, who had just taken a bathroom break, appeared at the sink to wash his hands. That may sound odd, but our bathroom sink was actually in what passed for our dining room. (Another story for sure.) Curious about what was causing all the commotion, Daddy took the liberty of picking up the picture, causing Miss Moore even more distress. After studying it for a second, he said, "Miss Moore, you being an unmarried lady and all, I don't understand how you even know what this is or why it upsets you." Grabbing the offending work of art out of Daddy's hand, face and neck glowing red, poor Miss Moore literally ran back to the schoolhouse. I don't think Mother spoke to Daddy for the rest of that day. I am not sure Miss Moore ever spoke to him again.

The Navajo had one belief that I always thought was unfortunate. It was considered extremely bad luck to be in the same area with a son-in-law. That meant there was no relationship at all between the two except fear of seeing each other. So, if Mrs. Manygoats was in the midst of trying to decide between a can of Carnation milk or a can of Pet Milk, but suddenly threw her Pendleton blanket/shawl over her head and made a run for the door, you knew without looking that her son-in-law had also arrived to do some shopping. All we could do was push her grocery choices to one side to await her return. That would not happen until he had his fill of "total chosie", treated his horse to a bag of oats, decided whether to purchase one or two plugs of tobacco and maybe even bought a new pair of Levi's.

Since Navajo sheep camps were often located in the same proximity with other family members, I often wondered how that worked out. There was no such taboo between mother-in-law and daughter-in-law. This son-in-law belief must have challenged the Navajo custom of always sharing whatever one had.

One of my sons-in-law drove all the way across the Valley this morning so he and my "baby" could spend a couple of social distance hours with us. The other son-n-law brought flowers on Friday (along with his wife, of course). These two men have enriched my life for many years, and I can't imagine not being able to communicate with them. My husband has a nearly hundred-year-old mother-in-law left over from his first marriage. This week we had a letter from Marge telling us how much she still thought about us and cared for us. Sometimes we white folk do get our priorities in the proper order! Happy Mother's Day to all and may we moms never forget to honor those good sons-in- law.

My mother swore me to secrecy on this tale, but enough time has passed, and circumstances have changed so drastically, that I can see no harm in "letting the cat (in this case, the body) out of the bag.” I also found mention of the incident in a book written by one of the Richardson brothers.

During the pandemic of the Spanish flu, the trader who was then at Kaibeto unfortunately passed away in the living quarters. His wife, knowing that if the Navajo found out that someone had died in the building, would never enter it again, locked up everything until she could send a rider bearing the sad news to some relatives in Tuba City. When this message reached the dead trader's younger brother, he hurriedly procured a "touring car" and by three o'clock the next morning had smuggled his brother's body away.

This all happened in 1919, some fifteen years before my parents appeared on the Kaibeto scene. Even so, I feel it is worth mentioning for a couple of reasons. I was married before Mother ever told me this story, along with the aforementioned secrecy clause, because she said that even then, if word got out, it could ruin our livelihood. This shows how deeply ingrained the belief about the "chindi" of the dead was planted in the Navajo culture. It is also a tale of our own times and what we are experiencing now. It is very unlikely that poor trader ever had a proper burial service and even more likely that the courageous wife had to carry on alone to keep the post running until new management could be found. Tomorrow I will talk about how my parents came to be in charge of Kaibeto and I assure you that is a much happier tale.

My parents met and fell in love at the wonderful little "off reservation" spot on Highway 89A North called Cameron. My dad's mother worked there as the hotel hostess and my mother was one of her associates. The proper terms would probably be head hotel maid and plain hotel maid. This is my parents love story, so forgive me for glamorizing a bit.

My father came west to visit his mom and the way the story was always told to me was that he took one look at the lovely dark eyed, brunette part Iroquois assistant and declared "That is the woman I am going to marry." There may have been a little more to it than that. My grandmother had managed to marry off five of her six surviving children and was probably wondering why this eldest son, now in his early forties, was not settling down and providing grandchildren. Since he had shown absolutely no inclination toward matrimony up to this point, it makes sense that there was some sort of encouraging influence.

This was still the time of the Great Depression, so "happily ever after" usually came with a catch or two. I am sure that Daddy was in dire need of a job, and it appears Mr. Richardson, who owned Kaibeto at the time, was weary of running out of family and friends to staff one of his most desolate posts, and Daddy was willing and able. No festive ceremony marked the occasion and with only a marriage license from the courthouse in Phoenix, it appears the newlyweds may have spent their honeymoon in a tent pitched between a very run down Kaibeto Trading Post and the mesa it depended on to keep it stable.

It was decided that the bride should be kept in the manner in which she was accustomed, and this included indoor plumbing and a kitchen with running water. There are quite a few pictures of the resulting renovations with the bride looking reasonably happy. It is what these pictures don't show that is amazing. A great deal of excavation would have been needed to add on the required amenities, but nothing like a backhoe is ever present. I don't know for sure, but I am almost certain that a great many Navajo men and a great many shovels were involved.

The things that keep me awake at night! Last night as I was mentally reviewing the layout of our trading post living quarters, it occurred to me that our kitchen should have been filled with water each time we had a decent rain. As noted yesterday, once it was decided to add on to the original building, a lot of digging had to be done. At some point someone decided enough sand had been removed to make space for a bathroom and kitchen. Walls were cemented almost to the top except where a row of windows were installed. When all was said and done the bottom of the windows ended up being level with the ground. This resulted in a huge slope of a yard with the lowest point ending by the kitchen door.

My memory fails me here. Perhaps we just knew better than to open the kitchen door when it rained. One had to step down to enter the kitchen from outside and then step up again to enter where the old structure connected with new. Same with the bathroom which really wasn't a bathroom at all for it never contained a bathtub. Aside from the obvious piece of equipment, the room was outfitted only with a pipe which dispensed cold water. Maybe someone intended to install a sink there one day, but the sink ended up in a quaint little room that was part of the original building.

This room was little more than a hallway between the old living room and the new kitchen. The enormous sink fit okay but was visible from any part of the living room. Once you used the bathroom, in order to wash your hands or anything else, it was necessary to step out of the bathroom, step down into the kitchen, navigate that space, then step up into the funny little room and perform your ablutions in full view of anyone who happened to be in the living room. Or you could go the opposite direction which meant you stepped up into the only bedroom and wended your way around the furniture in the living room before entering the sink room. Of course the sink was cold water only, but it did have a nice little ledge to hold the bowl where Daddy's dentures spent each night.

The door to the trading post was at the far end of the living room and one had to make three big steps down in order to enter there. Between trading post and warehouse there was another foot and half drop. Round and round we went, day after day, never missing a step and not giving a thought to our quadruple level existence. The only casualty we ever had was when our two-year-old fell down the steps from the living room and opened up quite a cut by his eye. He still guilt-trips me because I allowed the local Mormon Missionary, who had once been in training to be a doctor, tend to his wound. I keep telling him that the scar only adds to his rugged, manly charm.

Each Navajo family had at least three dogs, all of questionable breed, and every one of them earned their keep by being expert sheep herders. We didn't sell dog food. I doubt that it had been invented yet. So most of those dogs probably had a pretty good hunting instinct to supplement their diet.

I doubt the Navajos understood our relationship with our dogs who shared our lives and ate our vittles. One of them was Lollypop, a chubby little chihuahua given to me by Glenn, the son of the trader at Tonalea. Glenn never made it back from WWII and that is probably one of the reasons my parents tolerated Lollypop. From the time I received her, she became my baby. I constantly dressed her in doll clothing, wheeled her around in my doll carriage and put her to sleep at night in my doll bed. She put up with all this without a whimper or a growl. She adored me and mourned for days every fall when I became old enough to leave for school. She tolerated my mother and that was probably because she was smart enough not to bite the hand which fed her most of the time. Other than that, Lolly hated anything that breathed and moved, especially if it had two legs. Just entering the same room with her earned a person a snarling growl and a view of a mouthful of gleaming needle teeth.

Every once in a while, someone would forget to close the gate to our big yard and Lolly would go exploring. My discovery of her absence would be announced with screams and hysteria that disturbed the peace and tranquility for miles around. Daddy would call on Jack Hudson, who was not only our handyman, but also had the ability to track an animal or person many days after they had been in the area. In due time, here would come Jack, holding Lolly straight out as far as his arms could reach, while she hacked away at his shirt cuffs and glove tops. He would gently deposit Lolly behind the gate, double checking to make sure it was locked and report "mission accomplished" to Daddy. I suppose Daddy paid Jack a whole dollar for each day he worked--not bad wages for the time. I suspect that on "dog days" Jack may have gone back to his hogan with several silver dollars in each pocket.

Wool season usually started about the time I got home from school in the spring. I never got to see much of the shearing, but my impression was that it only took a few minutes for the fellow wielding the shears to finish the job and then reach for another disgruntled sheep. All this wool was then stuffed into a gigantic gunny sack provided by the trader and then transported by pickup or wagon to the nearest trading post. Each of these sacks could hold between 250 to 300 pounds of wool that were weighed outside on an enormous scale. There was always quite an audience for this event and every trader was center stage.

Not often, but once in a while, one of the sacks would weigh in quite a bit over 300 pounds and then the drama would begin. Out would come Daddy's pocketknife and a huge surgery would immediately be performed. The "patient" usually had one of three conditions. The wool would be soggy and wet. The wool would be liberally laced with sand. Or the most terminal and hardest to deal with, the wool would be interspersed with a great many small stones and pebbles. There were never any hard feelings, and audience and trader alike would have a good laugh. Daddy would state how much weight he was going to deduct, plus a small amount for our faithful Jack Hudson to "cure" the condition by removing the foreign bodies and resacking the wool.

Back inside the store, Daddy would bring out the account of how much the seller owed from his winter of trading and deduct the wool price. There was seldom anything left over and if there was, it was usually traded on the spot for flour, coffee, and other staples. The Navajo had to have absolute trust in the honesty of the trader, and I am proud to say my daddy had one of the best reputations on the Rez. He didn't mind playing the game, but he never played to win. Tomorrow we will find out about what happened to all that wool.

The wool sack population grew quickly and soon there were as many as fifty piled by the trading post front door. Each one bore a large KTP (for Kaibeto Trading Post) along with its weight in giant black letters. That stack of sacks was a wonderful lounging place for all the husbands who waited for wives to complete their shopping. What better vantage place to catch sight of your mother-in-law in plenty of time to slip away before she spotted you? At night it was a star gazer's dream for me as I reclined on the topmost bag and watched the heavens ever revolving majesty. All very romantic, but those sacks also represented the survival of our enterprise and had to be sold for a profit.

Daddy then had one of his biggest challenges before him. In order to contact a buyer and secure the best price possible, he had to use the telephone. Trading posts were the only places having phones. I am not sure how many posts shared our line, but at least a dozen. Each post had its own "ring" (ours was a long-short-long) and of course your ring sounded at the same time in every other post along the way. Those of you who ever had a party line might have some idea of this if you quadruple the possible complications.

The phone looked like a wooden box with a mouthpiece sticking out in front and a receiver attached to the side. There was also a little handle on the side for cranking out whatever ring you wanted. One very long crank was supposed to alert the operator from Flagstaff. Daddy would start there, hoping to reach his buyer. This worked about five percent of the time. Once this minor miracle was achieved, he had to make himself understood. This was achieved by inhaling until his face was purple and then shouting until both eyes were dangerously protruding. Once the price he was going to be paid was settled, that was it. There was no contract to be signed or other legal considerations. A simple gentleman's agreement sufficed to guarantee our business would survive another year.

Jean DeJolie is on my mind today. I didn't know Jean, but as one of five elderly Navajo ladies pictured on Facebook yesterday that DeJolie name means that I knew a great many of her family. Perhaps the Bob DeJolie I knew was her grandfather. Or there is a slight possibility she was one of the only two girls born into the DeJolie family after twelve boys.

The DeJolie's were one of those families with a surname that obviously had been handed out to them somewhere along the way as they struggled with the white man's idea of civilizing and controlling Native Americans. DeJolie was definitely a unique name for a Navajo. Their eldest son, born about 1934 was Charley and ended up graduating from the University of New Mexico. This was after he had graduated from Exeter Academy in New Hampshire with full scholarship. I think the next son was Harry and he is the father of award-winning photographer LeRoy DeJolie. Almost every year when I returned home from school, I would be greeted by a new DeJolie--always male. My mother and Mrs. DeJolie always seemed to think this was hilarious. I do know there were a full dozen boys before one of Daddy's letters mentioned that Mrs. DeJolie had given birth to a girl, and he figured that production would now cease. If I remember correctly there was yet another girl after that and then one more boy.

Sadly, the point of all this is that I can only speculate on where Jean DeJolie fits into the DeJolie family tree. Her picture was there yesterday because she is one of those who succumbed to the virus. So I memorialize her and honor her as representative of all the grandchildren and great grandchildren of those I have been writing about. May God keep them safe, along with those few elders who were there when I was.

Names--we all have trouble remembering them, putting the right face to the correct name, etc. The old time Navajo got around all that by believing that it was bad luck to call each other by name. If I were conversing with a Navajo friend and wanted to mention my father, I would not say "Hosteen Jones went to buy sheep today." Even though Hosteen was a term of respect, it would have been more respectful and better manners to say, "That man, who is my father, went to buy sheep today".

This bit of Navajo etiquette caused something of a problem when it came to keeping accounts at the trading post. We really needed to keep accurate track of who was charging all that hay and canned tomatoes and yards of velvet. By the time my parents took over Kaibeto, most accounts did have names attached, but there were a few among the very elderly who still refused to tell us their names. Out of respect for their advanced ages, none of their relatives would divulge them either.

Daddy solved the problem by tagging them with one of their physical characteristics or something from their lifestyle. Thus, we had "Lady Big Nose" who although bent with age and tiny in stature had inherited a stately nose befitting a high-ranking chief. We also had "Old Joe on Top", a sweet natured and very elderly man who chose to live alone in his hogan which was situated on top of our very near mesa. Obviously, "Hosteen Smallpox" had the scars from a childhood bout with that insidious disease and "Missing Fingers" had once upon a time been careless while chopping wood. These names were given thoughtfully and respectfully with no intention of teasing or ridicule. I doubt the recipients ever figured out how we kept them all straight.

One other part of the Navajo culture which would have stood them in good stead today was that hand shaking or embracing when meeting was not considered good manners. Out of respect for the white man's culture a, Navajo would softly clasp your hand when you offered it. Eye contact was also considered bad manners. Emily Post would have left in a hurry had she ever visited us. Thank God we have figured out that a lot of Emily's rules were nonsense, and we are realizing the Navajo culture was far more considerate of our human state.

I am looking at them now--a bit lumpy, definitely crooked with uneven edges, tightly woven in some places and too loose in others. They have been with me since childhood and one of them was just the perfect size to cover my "Monkey Ward's" doll bed. This trio is one of many "starter rugs" Daddy bought from beginning weavers. All traders bought rugs from Navajo weavers, and some were magnificent in design, perfectly symmetrical and feasts for the soul. Many others were saddle blankets which were nicely woven, colorfully striped but with no particular design.

If I remember correctly, saddle blankets had to be exactly 36 inches by 32 inches. I do remember that the big yard stick was always involved when we bought one. They accumulated quickly and Mr. Richardson at Cameron was always glad to get them as the tourists who stopped there snapped them up almost as soon as they arrived. A tightly woven saddle blanket with correct dimensions brought the weaver $3.00. One not quite so pristine might only bring $2.00. The beauties could take more than a half day of dickering, but I don't remember any of them ever earning the weaver more than $20.00.

Those great weavers had to start somewhere, so I am almost sure that every trader did as my parents did and encouraged little girls by purchasing their sometimes downright ugly first attempts at the loom. The quarter they received would buy a nice box of Crackerjack and several days’ supply of penny candy. Mother could never bear to throw one of these creations away. She used them everywhere like the crocheted doilies popular in Anglo homes during those days. We gave them to visiting relatives who seemed to view them as the treasures they were.

Of my three surviving rugs, two are gracing my houseplant collection and one (the doll bed one) covers a foot stool. They defy their almost eighty years of existence by looking exactly as they always have. After the husband and the dog, they just might be the things I would grab if this place ever caught on fire!

Every trading post was also a pawn shop. At Kaibeto, squash blossom necklaces, concho belts, and strands of coral beads all nested with each other in a big white cupboard located next to the penny candy and Baby Ruth bars. For some pieces that cupboard was almost a permanent home, for as soon as Mrs. Nez or Hosteen Manygoats had sold their wool or lambs and paid to redeem their pawn, they had to again begin the process of feeding their family.

Those were the days when there was no worry about fake turquoise, and every necklace or belt was always worth far more than the dollar amount held against them. There was a rule, or perhaps it was a real legislated law, that the trader could not sell any pawned item until it had been housed for a full year. Daddy paid not the slightest attention to this and as long as the jewelry owner was alive he or she had no fear of his precious heirloom being sold. Some of the pieces were in there so long, it would have taken a week of polishing to remove the tarnish.

When someone died without redeeming their jewelry, Daddy always made sure there was no family member who wanted to redeem it. Due to the "chindi" belief, it was very rare to have someone want a dead relative's necklace, no matter how little owed. Then and only then, would he offer it to one of our visiting relatives or friends and never for more than the amount owed. Pawning was definitely not one of our more profitable efforts. An interesting sideline is mainly what it was.

When Jim and I retired we moved to a location only a few miles from the Rez. One day a Kaibeto lady came by our place and wanted to pawn her squash blossom necklace for two hundred dollars. Even though I wasn't sure of the authenticity of the piece, the trader in me just couldn't turn her down. Weeks turned into years, and Jim kept telling me to see if I could sell the necklace. One day as I returned from a visit with our Phoenix family, my husband sheepishly handed me $200.00. It seemed Mrs. Sly had come by for her necklace with no apologies, taking it for granted it would still be there. Guess she figured "daughter like father." It gave me a good feeling and I didn't even say "I told you so." (At least not very loud.)

Senator Goldwater was not the only celebrity to visit our trading post. Several years after WWII a Navajo fellow named Carl Gorman was a frequent visitor. Over grazing was always a problem in our area and Carl had some sort of job with the BIA which required him to visit around the Rez and make sure no Navajo was in possession of more than the approved number of livestock. Carl had a son named Rudy who was a couple years older than I and sometimes Carl would drop him off to spend the day with us while he worked. Rudy and I were not that compatible as all he wanted to do was draw pictures on the cardboard sections out of candy bar boxes which Daddy saved for him. He could not understand why I couldn't just pick up a pencil, as he did, and make magical designs and life-like drawings of people and animals. If we played in the plentiful sand in the yard, I was content to make hills and valleys and roads for my toy cars. Rudy made Taj Mahals and castles complete with moats.

Losing patience with me one day, Rudy started giving me lessons on how to whistle. From the beginning I was a pretty apt student, and Rudy had a whole afternoon for pursuing his artistic endeavors. That was before I figured out that one could whistle and be a pest at the same time.

Rudy often left me a drawing or two, and I filed them away with my paper dolls and other important possessions. After a while, his father Carl was transferred, so Rudy didn't come any more. Next time I saw him we were in the same writing class at NAU (Arizona State Teacher's College back then). He was active in the Drama Club, and I was busy playing the flute, so our paths didn't cross often. By now you have probably guessed this one. Rudy was none other than R C Gorman who has paintings in high places in Washington D. C. and all over the world. What happened to those cardboard drawings he gave me? I tossed them along with other childish things when I went away to college.

Having known Rudy makes me wonder a couple of things. If he hadn't taught me the joy of making pretty music with my lips, would I have ever fallen in love with the flute? More important, if I had kept those drawings, would my children have had a much easier time paying for their educations? Rudy died maybe as much as ten years ago in Taos, New Mexico, where he had lived for many years.

One of you did a bit of research yesterday and found out that the Carl Gorman I mentioned had been one of the original Code Talkers who used the Navajo language to communicate our military’s secret messages. The enemy never broke the code. I am not sure how, but we always knew that Mr. Gorman was a Code Talker. We knew of no others.